Africa’s Tech Edge

How the continent's many obstacles, from widespread poverty to failed states, allowed African entrepreneurs to beat the West at reinventing money for the mobile age

It’s a painfully First World problem: Splitting dinner with friends, we do the dance of the seven credit cards. No one, it seems, carries cash anymore, so we blunder through the inconvenience that comes with our dependence on plastic. Just as often, I encounter a street vendor or taxi driver who can’t handle my proffered card and am left shaking out my pockets and purse.

When I returned to the United States after living in Nairobi on and off for two years, these antiquated payment ordeals were especially frustrating. As I never tire of explaining to friends, in Kenya I could pay for nearly everything with a few taps on my cellphone.

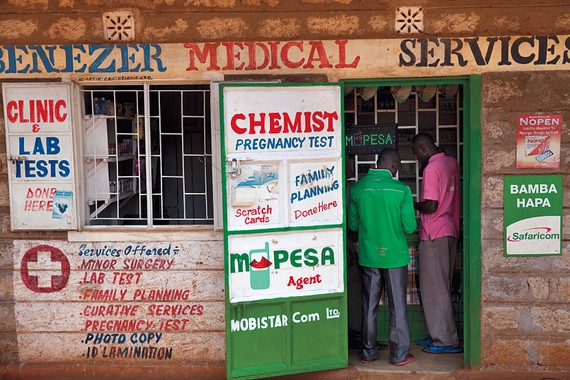

Every few weeks, I’d pull cash out of my American bank account and hand it to a contemplative young man stationed outside my local greengrocer. I’d show him my ID and type in a PIN, and he’d credit my phone number with an equivalent amount of digital currency. Through a service called M-Pesa, I could store my mobile money and then, for a small fee, send it to any other phone number in the network, be it my cable company’s, a taxi driver’s, or a friend’s. Payments from other M-Pesa users would be added to my digital balance, which I could later withdraw in cash from my local agent.

For me, M-Pesa was convenient, often simpler than reaching for my credit card or counting out paper bills. But for most Kenyans, the service has been life-changing. Kenya has one ATM for every 18,000 people—the U.S., by contrast, has one for every 740—and across sub-Saharan Africa, more than 75 percent of the adult population had no bank account as of 2011. When Safaricom, the major Kenyan telecommunications firm, launched M-Pesa in 2007, pesa—Swahili for “money”—moved from mattresses to mobile accounts virtually overnight. Suddenly, payment and collection of debts did not require face-to-face interactions. Daylong queues to pay electric- or water-utility bills disappeared. By 2012, 86 percent of Kenyan cellphone subscribers used mobile money, and by 2013, M-Pesa’s transactions amounted to some $35 million daily. Annualized, that’s more than a quarter of Kenya’s GDP.

M-Pesa isn’t the first mobile-money service. The Philippines has had at least rudimentary mobile money-transfer systems since 2001, but nine years later, fewer than 10 percent of Filipino mobile users without bank accounts actively used them, while the long tail of mobile-payment systems has already transformed Africa. Parrot programs like Paga, EcoCash, Splash Mobile Money, Tigo Cash, Airtel Money, Orange Money, and MTN Mobile Money have sprung up in several African countries. Even government has elbowed its way in: the Rwanda Revenue Authority has introduced a service that allows citizens to declare and pay taxes right from their cellphones.

Mobile money exploded in Africa because the continent’s cash economy was ripe for disruption. Even as the number of city dwellers wishing to send money to rural relatives surged, the prevailing technology was still pressing an envelope of cash into the hands of a bus driver or trusted friend heading home. Some paranoiacs would wedge a parcel above the wheel of a bus, sending the intended recipient instructions for how to retrieve it many dusty miles later.

Money transfer was just one problem for the millions of informal-sector workers who had no standardized tools for managing cash flow—no checking or savings accounts, no credit cards. “You have a huge informal economy—a lot of people who are not part of the banking system,” Lohini Moodley, a co-author of McKinsey’s “Lions Go Digital,” a report on technology in Africa, told me. This gray economy has historically operated using a blend of ad hoc and do-it-yourself financing processes, with cash and IOUs featuring prominently.

But, first in Kenya, then around the continent, mobile money has changed everything. Perhaps most important, M-Pesa and its cousins offer a long-sought ability for individuals in poor countries to build assets. If you squint, digitally stored currency looks like a simple checking or savings account. M-Pesa has nearly 80,000 agents, like my man at the grocer, who function as tellers for a massive virtual bank.

This competition has not gone unnoticed by the African banks that once ignored the bulging mass market: between 2005 and 2009, the number of bank branches in Kenya roughly doubled. Across Africa, new ventures are using mobile money as a platform to facilitate other services like insurance, analytics, consumer credit, and e-commerce. “There’s a huge appetite from people to conveniently and reliably access services they are already accessing in less convenient and more expensive ways,” Rachel Balsham, who does business development for the Mauritius-based mobile-finance start-up MFS Africa, told me.

In a pleasing inversion of development logic, Africa has leapfrogged way ahead of the wealthy world. Though about half of Americans now have smartphones—driving major changes in the way we learn, work, and socialize—mobile innovation has only grazed the realm of finance. A 2012 report on global financial habits found that the most technologically advanced economies have actually been among the slowest to catch on to mobile money. Across sub-Saharan Africa, 16 percent of adults said they used mobile money. In all other regions, including Europe and the Americas, by contrast, that figure was less than 5 percent.

Compared with Africa’s mobile revolution, digital financial innovation in the U.S. doesn’t seem all that innovative. Sure, you can photograph a paper check to deposit it. Some apps link bank accounts to sleek budgeting interfaces. But the majority of third-party mobile apps simply replicate the desktop experience of balance transfers or bill paying. PayPal’s core product has remained roughly unchanged since the company was founded in 1998, while Square, the fast-growing service whose mobile attachments allow vendors to accept credit and debit cards for lower fees, hasn’t fundamentally changed the market—just adjusted revenue shares.

How did a continent still struggling to guarantee clean water and reliable electricity beat Silicon Valley to this groundbreaking mobile solution? After years of reporting on African innovation, I came to a conclusion both surprising and obvious: necessity drives creativity, and institutional failures accelerate the process of experimentation and problem solving.

In contrast to the stereotype of a poor and passive continent, the people I encountered across sub-Saharan Africa deploy clever work-arounds to make ends meet, and to keep the informal economy humming. A vuvuzela can be twirled in a bucket to wash clothes. Tire treads become sturdy sandals. Bottle caps are used as checkers. Forced to do more with less, African consumers rarely limit themselves to using products in the ways they’re marketed.

The genesis of mobile money is a useful example. From the moment cellphones hit the Kenyan mass market, about 15 years ago, consumers began swapping prepaid calling minutes to buy goods and barter for favors. When M-Pesa launched, it broadened and formalized this practice. Kenya’s flat-footed banking sector and lax governmental regulation allowed the service to scale up with almost no intervention.

This is par for the course in the region, where the lack of infrastructure investment during the 20th century created all sorts of vacuums to be filled by the 21st-century digital economy. “In Tanzania, where I’m from, I see cool technology more and more,” says Mbwana Alliy, who was an angel investor at i/o Ventures, in San Francisco. “Remember, we don’t have to have a PC revolution—we skipped that. The catch-up is more interesting than anywhere else in the world.”

Call it the imagination differential: more-advanced economies may never have dreamed of using airtime as currency, or a telecom as a bank. Western privilege can actually prevent truly disruptive tools from evolving. Alliy, who now lives in Nairobi, where he runs a venture-capital fund that he co-founded to support early-stage tech ventures in Africa, described bringing Russel Simmons, a co-founder of Yelp and an early employee of PayPal, on a visit to Kenya. Despite Simmons’s having worked at a pioneering payment company, Alliy told me, he was taken aback by M-Pesa’s prevalence.

Thanks to mobile money and the culture of innovation that grew up around it, East Africa—dubbed the “Silicon Savannah”—is now a frequent stop for tech investors. Eric Schmidt, Google’s executive chairman, has visited the company’s Africa offices and praised local innovation. News in February that Facebook would acquire WhatsApp, a smartphone messaging service ubiquitous in Africa, confirmed the importance of tech trends in emerging markets.

One of the more prominent trends today is using mobile payments as a platform for more complex products. Econet Wireless Zimbabwe recently rolled out a new service that allows customers to use its EcoCash platform to move money into interest-earning savings accounts. Safaricom partnered with the Commercial Bank of Africa on a similar service. In East Africa, farmers pay agricultural-insurance premiums and receive reimbursements using mobile-money platforms. Orange Mali partnered with MFS Africa to launch an insurance program for pregnant women.

Mobile payments also offer companies a leg up on consumer data and analytics. “Cash is dumb,” Ben Lyon, a co-founder of Kopo Kopo, a Nairobi-based company that helps small businesses accept mobile money, told me. An electronic financial footprint, by contrast, provides data that help merchants understand the purchasing habits of Africa’s rising consumer class—and could seed a rudimentary credit-reporting system.

Mobile financial services are projected to generate annual revenues of $19 billion by 2025. Multinational corporations, fearing what a mass defection from plastic would mean for their growth prospects, have begun sniffing around this complex ecosystem. Visa is launching mobile point-of-sale devices—handheld swipe machines that will read credit cards, similar to Square’s—to increase Visa’s rate of acceptance in Africa. MasterCard, meanwhile, worked with Kenya’s Equity Bank to issue 5 million plastic payment cards. The company also partnered with the Nigerian government in an attempt to issue a national ID that would double as a prepaid debit card.

The African payment entrepreneurs and experts I spoke with believe they can maintain their home-field advantage. “As smart as they are, their legacy system is their downfall in a place like Africa or Kenya, where there’s a lot less data and information to go on,” Mark Kaigwa, a consultant who focuses on technology in East Africa, told me, referring to the big payment processors, like MasterCard. “Your appetite for risk, your appetite for experimentation, for piloting things, needs to be higher, and your commitment needs to be more long-term.”

It’s tempting to assume that mobile financial services haven’t evolved in the wealthy world because they aren’t needed, but the evidence suggests otherwise. Despite the abundance of traditional banking and financing mechanisms in the United States, in 2011, the poorest 30 percent of Americans were, to use an industry term, underbanked—unable to access credit and financial services within their means. Most check-cashing outlets and short-term lending schemes with three-digit interest rates are worse than stowing cash under a mattress. But for the unwilling or the undocumented, the cash economy is the only one available.

Exporting mobile money to the United States, however, entails a slew of challenges that its creators did not face in Africa. Need drove the invention of M-Pesa and its counterparts, but regulatory ambiguity ensured it could scale. Even today, mobile-banking laws in Africa are evolving slower than the technology itself. One hazard, regulators believe, is that mobile payments can be used for money laundering. While much of this risk is diffused by ID cards, PINs, and caps on transfers, it was not until 2011 that Kenya legislated capital requirements for mobile banking, and only in 2013 did the government begin to tax mobile transfers. Other countries in Africa have been stricter about which entities can serve as mobile financial institutions, but since telecoms are not traditional banks, they fall into a regulatory gray area.

In the United States, however, banking laws are much less malleable, and any activity that smells like banking is subject to a significant burden of compliance with post-crash policies designed to protect consumers. Allowing telecoms or tech companies to act like banks may involve new legislation. Given this headache, mobile money in the U.S. might end up looking different than it does in Africa, perhaps involving partnerships among wireless carriers, hardware companies, and banks. But the bar has been set, and the West now finds itself in the unfamiliar position of looking to Africa for technological inspiration.